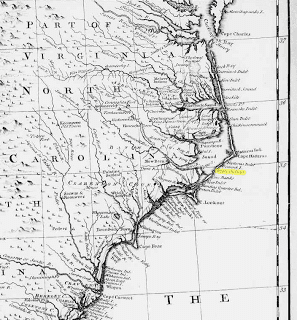

Many Spanish

merchantmen sailed our coast, taking advantage of the Gulf Stream. It's

recorded that at least three met their fate during the storm of August 18,

1750: The snow El Salvador sank near Cape Lookout, the Neustra de la

Solidad went ashore on Core Banks and the Neustra Senora de Guadaloupe went

ashore in Ocracoke. The most convincing proof of these wrecks is a Spanish coin

that was found on the beach at Cape Lookout in 1992.

By Doug Wilson

Havana harbor was a hotbed of activity as the

1750 Spanish treasure fleet readied itself for the long and perilous voyage to

Spain. It was August and the hurricane season was already upon them ... the

vessels assembling beneath the mighty guns of Morro Castle numbered just seven.

They had been placed under the overall command of Captain-General Don Juan

Manuel de Bonilla, a brave and courageous man but one occasionally prone to

indecision.

The most important ship was the Admirante,

or "admiral" of the fleet, Bonilla's five-hundred-ton, four-year-old,

Dutch-built Nuestra Señora de Guadeloupe (alias Nympha).

She was owned by Don Jose de Renturo de Respaldizar, commanded by Don Manuel

Molviedo, and piloted by Don Felipe Garcia. Guadeloupe was a

big ship, and had been allotted a substantial cargo of sugar, Capeche dyewoods,

Purge of Jalapa (a laxative restorative plant found in Mexico), cotton,

vanilla, cocoa, plant seedlings, copper, a great quantity of hides, valuable

cochineal and indigo for dyes, and most importantly, as many as three hundred

chests of silver containing 400,000 pieces-of-eight valued at 613,000 pesos.

Among her passengers was the president of Santo Domingo, Hispaniola, as well as

a company of prisoners.

So writes Shomette in his enlightening tale of

a routine Spanish treasure shipment casting its fate to the

wind. Another account reports just five ships and names only de

Guadeloupe. There were as many as eight ships in the armada under Bonilla's

command:

- Nuestra Señora de Guadeloupe alias Augusta Celi or Nympha,

with Captain Molviedo, owned by Respaldizar;

- the King's 50-gun frigate, Nuestra Señora del Carmen alias La Galga, Don

Daniel Mahoney, captain;

- the King's small brigatine or Zumaca schooner Nuestra Señora de la Merced, or La Mercede, Don Antonio Barroso,

captain;

- a Portuguese ship, Nuestra Señora de los Godos alias Arinton, captained by Don Pedro de Pumarejo

and Don Francisco de Ortiz;

- a small Portuguese frigate with Cartagena registry, San Pedro or Saint Peter, John

Kelly, commander;

- a Cartagena registered Snow packet boat, El Salvador alias El Henrique, owned

by Don Francisco Arizon, Don Juan Cruanio, captain, wrecked 15 leagues

north of Ocracoke Inlet;

- a small frigate, Nuestra Señora de la Soledad y San Francisco Xavier, owned by Don Jose de Respaldizar and Don

Manuel de Molbudro; and possibly,

- a sloop from Compeche, La Marianna, Don Antonio Ianasio de Anaya, commander.

|

| Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

The small armada carries important passengers

like the Governor of Havana and family, the quartermaster general of Chile and

family, a treasure and luxury item shipment of the King's own company, and a

silversmith as representative of another precious cargo's owner. They are

similarly laden with more Spanish Reales (known as pieces-of-eight), valuable

commodities, diamonds, and precious metals, all extracted from the conquest of

Central and South America. But it is de Guadeloupe that is the

greatest prize, with more than 12 tons of silver in 400,000

pieces-of-eight, each of which weighs one ounce. The early American silver dollar is based upon this coin

and its weight / value in silver. That is why 25¢ is known as two bits. Two

pieces (or bits) of eight make a quarter.

The King is anxious for a successful voyage and

transit of his goods. These valuables are sorely needed to replenish the

Spanish treasurer from years of conflict with England and France, known in

Europe as the "War of Austrian Succession", in the colonies as

"King George's War." Mother Nature has other plans. This time,

Bonilla's own flagship and its precious cargo will be jeopardized by the fierce

weather. It will force him to trust a former enemy in a desperate encounter

with English privateers turned pirates - including some FitzRandolphs and a

young Joseph (Thorne) Jackson of Woodbridge, New Jersey, that are the original

subjects of my research.

This story draws from several different accounts

of the events retold from personal records and government documents. The

Spanish perspective is taken from Bonilla's log and Spanish documents as

referenced in Donald Shomette's recent compilation of shipwreck

tales. The English and

Dutch perspectives are contained in colonial government correspondence and news

articles. The Jersey pirates' tale is told by shipmate William Waller in

his 1750 testimony to the New Jersey Provincial Justices.

The New Englander sloop story was passed down in the family of one of the

ship's owners. But there are also two jokers in the pack, Owen Lloyd and

William Blackstock. It is Blackstock, alias William Davidson, who tells their

story in his 1750 testimony before Dutch West Indies Justices.

He'll also tell us how some of the treasure gets buried on the "real"

Treasure Island - and what happens to it next. Be sure to follow the links to

learn more about these stories.

DANGEROUS SHOALS

On August 18, 1750, Bonilla opts to set sail despite

worsening weather. Perhaps he is hoping the weather will stay out of his way or

keep pirates at bay. They pass Cape Canaveral at 29° North latitude on the

Florida Penninsula by the afternoon of August 25 when the fleet encounters dark

skies and blustery winds out of the north. The winds turn to gale force of a

shifting direction that batter them from the southwest by evening. A full day

later, Los Godos is the first to succumb to the tempest turned

hurricane. She takes on more water than her pumps can handle. Then waves

finally break her tiller and winds rip her sails. As control is being lost, her

captain orders a lightening of the load, with the largest livestock first; then

cannon, oven, and damaged boats. She is crippled and temporarily out of sight

of the fleet. San Pedro fares much the same. (Shomette, p21)

Three days after the first signs of bad weather,

on the 28th, Los Godos makes contact with Guadeloupe as

the separate ships continue to be battered by wind and waves not far from the

Carolina coast. With nightfall, all contact is lost forever. The forces of

nature continue to disperse the vessels' paths. Both vessels are driven

relentlessly nearer the dangerous shoals of North Carolina's Outer Bank Islands

at 33° North. The crews, passengers, and prisoners are left to pray that they

do not share the watery fate of the livestock.

On the 29th, the snow El Salvador is

the first ship lost, breaking up in the waves on a beach near Topsail Inlet.

Only a few crew escape, washed ashore with eleven boxes of the King's own

silver. A Bermuda registered sloop captained by Englishmen Ephraim and Robert

Gilvert survives a sandbar to anchor near the wreckage and scavenge it for

sails and several chests of treasure. Soledad is lost south of

Ocracoke near Drum Inlet, but all the crew and fourteen chests holding 32,000

silver pieces-of-eight survive.

Guadeloupe stays afloat long enough for the winds to subside on the 30th.

Bonilla anchors the broken-masted Admirante of the fleet

several leagues south of Cape Hatteras. They weather out the storm tethered

there overnight. Bonilla assesses the degraded condition of his vessel the next

morning and realizes she needs considerable repairs in the protection of the

other side of the perilous Ocracoke Bar. High water and less wind might help

the damaged hulk with makeshift sail maneuver to a safer harbor.

But Bonilla risks mutiny of the crew and its

leader, boatswain Pedro Rodrigues. They plan to either run the boat aground or

throw the treasured goods overboard to ensure passage across the bar. Bonilla

holds firm, sending out a scouting party that yields a small boat and pilot to

assist them over the bar. Risking exposure to theft but to lighten the load,

Bonilla also orders the chests of treasure put ashore using Guadeloupe's pinnacle.

(Shomette, p24)

At the same time, but hundreds of miles up the

coast in New Jersey, a mariner named William Waller and one Margaret

FitzRandolph, both of Woodbridge, take out a marriage license on the 1st of

September. (NJ Archives, v22, p147) When the marriage occurs

or if there is a honeymoon is not reported. But within three weeks, the groom

will depart for the Carolina coast and an unexpected adventure with his new

bride's cousins. We will hear more of Waller as the source for much of the New

Jersey privateer's perspective in this story.

By the 3rd of September the disabled treasure

ship is maneuvered into the modest protection of the bayside of Ocracoke Inlet.

(Stick & Stick, p38) Bonilla and some of his

crew are ashore the first night when a "Bahamian snow named Carolina appeared

on the scene and quietly made fast to the ship." (Shomette, p31) The pirates grab only a few things

before being repulsed by the remaining crew, but Bonilla and de

Guadeloupe remain awkwardly stranded on the colonial English shore for

weeks.

Two weeks later and back up the coast in New

Jersey, Samuel Fitz Randolph sets sail

from Perth Amboy on September 19 in his sloop, Mary, of Woodbridge.

The crew includes Samuel's sons, Kinsey and Samuel Fitz Randolph, Thomas

Edwards, Benjamin Moore, Joseph Jackson (born Joseph Thorne), Silas

Walker, and William Waller - a newlywed for less than

three weeks. The destination and purpose of the voyage is unreported in

Waller's later testimony before the Provincial Court Justice Samuel Nevill.

A week later in North Carolina, Governor Gabriel

Johnston assembles his Council to get their support in dealing with Bonilla's

predicament and the state of affairs it has created on the Outer Banks. The

customs officers contend that the Spaniards unlawfully unloaded their cargo on

North Carolina soil and should be seized for duties and penalties. The Governor

suggests offering assistance and protection even though none has been

requested. Colonel Innes, a member of the Council most experienced in the ways

and language of the Spaniards, is sent to Ocracoke to investigate the situation

and Bonilla's needs.

On the way to Ocracoke, Innes learns that

the Bankers, the ungovernably independent inhabitants of the wild

and remote island chain, are planning to raid the wrecked Guadeloupe "in

force" for whatever they can salvage. Upon hearing the news from Innes,

Governor Johnston makes an immediate request for reinforcements from South

Carolina in the form of the British warship H.M.S. Scorpion. He

will seize the Bonilla's vessel to protect its cargo by force, if necessary.

While the provincial governments figure out what to do, some business interests

of South Carolina try to bring some action their way from the north. "A

man named Tom Wright had come up from Charleston, was mingling with the

Spaniards incognito, and was advising them to ignore the government of North

Carolina and ship their valuable cargo to Charleston instead." (Stick, pp38-39; Ballance, p15)

Following the storm from the south is a

seventy-five ton sloop, Three Sisters, captained by Zebulon Wade.

The ship was built as a trader in Cohasset, Massachusetts, by Aaron Pratt,

Stephen Stoddard, Israel Whitcomb, and Mrs. Binney. This was a step up in ships

for Wade, son of a sea captain and great-grandson of Nicholas Wade, the

immigrant that established the Wade family in Scituate 120 years earlier. (Burrage & Stubbs, p1420) Three Sisters is likely on

the return leg of her maiden voyage, a "trading run to southern

ports." The Vice-Governor of the Danish West Indies will later recall

seeing the ship in harbor there. The Three Sisters destiny

will take its crew to Ocracoake Inlet by September 3rd. Depending on the

timing, they could have witnessed the arrival of the "Bahamian snow

named Carolina" and the attack on de Guadelope that

night. These accounts are silent on that point.

Waller tells us that when Mary arrives

at Ocracoke, they see "a large Spanish Ship of about 500 Ton at an anchor

over the Bar" of Ocracoke Inlet. The ship appears to be in distress,

having lost the heads of her foremast and main masts. Her mizzen mast and rudder

were also gone. (NJ Archives, v16 , p276-280)

Shomette describes the encounter from the

Spaniards' perspective. In this version you will find that the Three

Sisters is called the Seaflower. It is hard to say which

name is correct. Seaflower is taken from a translation of

contemporary records, while the name Three Sisters was passed

on verbally for a hundred years before being recorded.

At this critical juncture, two bilander sloops appeared on the scene. One was

a New Englander called Seaflower, commanded by Zebulon Wade, of

Scituate, Massachusetts, the other a New Jerseyman from Perth Amboy named Mary,

Samuel FitzRandolph master and owner. Despite the piratical actions of the last

English visitors on the scene, and his own fears that

the newcomers might play another "scurvy trick," Bonilla guardedly

viewed the arrival of the two sloops as an opportunity. The winds remained high

and the water quite shoal in the shelter less cove, and his ship might be

bilged at any worsening of the weather.

With "the Intrigues and Artifices

of Pedro Rodriguez Boatswain having got most of the Men on His side and under

Pretence of going to Virginia," there seemed little choice. Calling his

remaining loyalists together for a conference, the admiral proposed employing

the two shallow-draft sloops "to keep his money and other effects on

board, 'till he could either hire or buy another ship." It was so agreed.

For some reason, perhaps to curry his favor, Rodriguez was sent aboard Mary to

negotiate an arrangement to carry the cargo to Norfolk. One of FitzRandolph's

crew, William Waller, of Woodbridge, New Jersey, served as interpreter. Within

a short time, Mary's master had agreed to transport the lading to

Virginia for a fee of 570 pieces-of-eight. A similar agreement was made with

the master. of Seaflower. Soon afterward the Spaniard returned with

fifteen hands in a launch to haul the two sloops alongside Guadeloupe.

On or about October 5, as the transfer of

treasure was under way, a certain Colonel Innes arrived bearing a letter from

Governor Johnston, summoning Bonilla to New Bern to answer charges of illegally

breaking bulk in the colony without permission. Bonilla, who had been expecting

assistance, not a summons, was stunned. Fortunately, having also been sent to

specifically inquire into Guadeloupe's situation, the Colonel

was not unsympathetic to the Spaniard's plight. He had become immediately

suspicious of the intentions of Mary and Seaflower and

expressed his fears to Bonilla that the sloops would attempt to run away with

the treasure. He even volunteered to take possession of them. In the meantime,

a sloop-of-war might be provided for the purpose of carrying the money to

safety. But to do so, it would be necessary for Bonilla to accompany him to

meet with the governor. The Spaniard readily accepted. Rodriguez, however, now

backed by many of the remaining crew and fearing that if the English got their

hands on the treasure neither he or his men would ever be paid, vehemently

protested and "would not suffer the Money to be removed."

Nevertheless, Bonilla set off immediately with the colonel.

Fifty-five chests of treasure and a

"substantial cargo of cocoa, cochineal, and sugar" had already been

transferred to Seaflower and upward of 54 chests to Mary.

Bonilla halts the loading operation and secures his goods in preparation for

his absence. He issues written instructions "to have the two vessels'

sails carried ashore where they would be guarded until his return, for without

sails the two sloops could not possibly leave. Then he ordered ten loyal armed

men placed aboard each vessel to prevent any underhanded actions. The holds of

both vessels in which the treasure chests had been stowed were to be barred,

locked, and kept under constant guard." (Shomette, p18)

While Bonilla was making arrangements for the

protection of the King's treasure, on shore some privateers are scheming how

nice it would be to take it for themselves. They are frequent travelers in the

waters between the Carolinas and Carribean commonly known as the Bermuda

Triangle. First they observe the stranded galleon, then the arrival of the sloops. But it is the effort to preserve the large ship's

cargo that gets their attention fixed upon the galleon. Knight describes

the scene for us.

William Blackstock, who also went by the name of

William Davidson, was born in Dumfries, Scotland. A mariner by trade, he had

sailed out of Rhode Island at the end of September, 1750, and put in at the

Ocracoke Inlet on or about the 1st of October.

When Owen Lloyd first approached him with a

proposition to steal-away with the two sloops, Blackstock made light of the

subject and passed Lloyd off as an idle schemer. But, with the departure of the

Spanish captain for New Bern, it became clear that Lloyd and his associates had

resolved to make good their plan. Upon consideration, Blackstock gave in to

Lloyd’s urgings and joined the plot. The conspirators were a hastily-assembled

collection of salt-encrusted rabble from up and down the Eastern Seaboard.

Among them was Trevet, a thickset Carolinian with a slow back-county drawl, who

Lloyd had chosen as mate. And then there was James Moorehouse of Connecticut, a

headstrong young Yankee; William Dames, a sharp-eyed Virginian; a shoeless old

sea-dog by the name of Charles; and Owen Lloyd’s brother, Thomas, who at the

stump of one knee wore

Coincidental to this

plotting and the salvaging of the Guadeloupe's cargo on

October 5, 1750, England and Spain sign the Treaty of Madrid, formally ending

11 years of hostility. Yet to be ratified, it will be eight months before the

Treaty will be announced to the Colonies with a copy published in a

Philadelphia newspaper. (Baynes, p743; Collections v.10, p.271) That treaty sets an

expectation of mutual respect and cooperation between the English and Spanish.

It specifically details these expectations in cases of piracy since a catalyst

in 1738 for starting the war was English outrage over Spanish piracy. Captain

Robert Jenkins reported to the British House of Commons how Spanish Coast

Guards boarded and pillaged his ship and abused his person. Upon holding up his

amputated ear as evidence, the conflict also became known as the War of

Jenkins' Ear. (Britannica) It would seem this cause is not the

motivation of Owen Lloyd and William Blackstock, however.

Read more ...

No comments:

Post a Comment